Promising clusters

GaaP. Government as a platform. There's a lot of chatter about it at the moment, it's got something to do with the future of public services in the UK, but what is GaaP? And why is anyone interested?

Where to start ...

... Tim O'Reilly? No.

... Public Servant of the Year ex-Guardian man Mike Bracken CBE CDO CDO, executive director of the Government Digital Service (GDS) and senior responsible owner of GOV.UK Verify (RIP)? No.

... Simon Wardley.

You get your money's worth with Mr Wardley. He's a trouper. DMossEsq has a nascent, muscular relationship with him ...

— David Moss (@DMossEsq) October 27, 2014

|

... and hats off to him, Mr Wardley does one of the best jobs on the circuit debunking management consultants. Treat yourself, now, for 13 minutes and 9 seconds:

Who says music hall is dead?

What Mr Wardley says in the video is:

- He can predict the future. He knows what's going to happen although, unlike a proper astrologer, he can't say when ...

- ... which means he can devise strategies for companies. What is a strategy?

- Strategies are what army generals have. How do they make them?

- They use maps. Does Mr Wardley have a map?

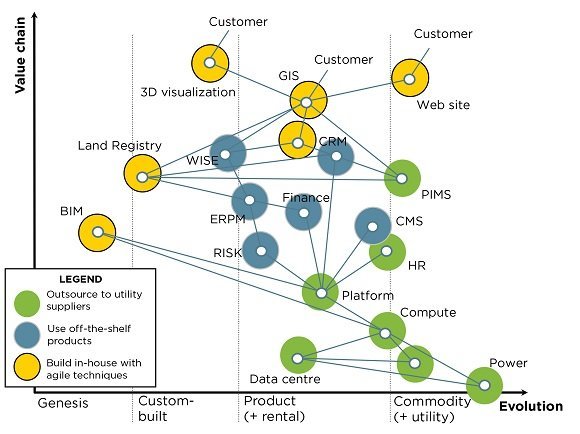

- You bet he has. See below. Companies are value chains, value chains consist of components, competition causes components to evolve and Mr Wardley maps the value chain-evolution surface.

Which brings us to Mark Thompson's What is government as a platform and how do we achieve it?.

Mr Thompson is another management consultant, like Mr Wardley, and he has worked out precisely how to achieve GaaP. He offers a "simple methodology":

We'll come back to the distinction between products and capabilities later. First, in case you thought we had taken a wrong turn and strayed out of the ballpark, note that it looks to followers of Twitter as though Mr Wardley advises GDS and Mr Thompson locates GDS at the heart of GaaP:

This approach is based on Simon Wardley’s work, extended to enable a clear distinction between “product” and “capability” from which we then derive a simple methodology for achieving government as a platform.

It's not clear how much Mr Thompson knows about GDS. He seems to be under the impression that GDS succeeded in deploying its 25 exemplar services:

For central government, the logical steward for these shared capabilities is the Government Digital Service (GDS) ...

Digital business change will be achieved to the extent that, stewarded and supported by GDS, everyone can gradually maximise shared capability (platforms), and minimise departmental “product” (bespoke services) ...

Common Capabilities ... Owned centrally in GDS (central plat) ...

Functions to be migrated to the growing set of shared capabilities (stewarded centrally in GDS) ...

GDS are a long way from securing "quick transformational wins" with the exemplars.

GDS has already achieved much in driving digital change in government – particularly in securing some quick transformational wins via the25 targeted service exemplars.

But Mr Thompson would be quite at home there when it comes to user needs, whatever they are. Like GDS, and everyone else, he thinks you have to focus on user needs.

He also thinks that user needs exist in a value chain. And that the job of Whitehall's generals is to "determine what components are required to meet those needs".

Although that includes some of the same words, it's not what Mr Wardley said. Don't confuse the two.

And it poses a problem. In Mr Thompson's value chain diagram, how do you distinguish a need from a component required to meet that need?

We've got a lot of circles with black borders, some of them are connected by black lines and some aren't, and one of them has an arrow coming out of the top. Which one is a need and which one a component required to meet a need?

What, you may ask, about the dark ellipse? Forget it. By Step 3, it's disappeared.

Meanwhile, why does the value chain axis range from "invisible" to "visible"?

Step 3 involves adding Mr Wardley's evolution axis to the diagram, thereby making it into a map.

These are the first three steps of Mr Thompson's "simple methodology for achieving government as a platform". At Step 4 we "need to apply this consistent logic to identifying whether we should be developing specific services or common capabilities".

Which brings us back to the products v. capabilities tension identified above. We need "a clear distinction between 'product' and 'capability' ...", Mr Thompson said, if you remember.

We shouldn't. You don't have any trouble distinguishing a product from a capability, do you?

The problem is exacerbated because Mr Thompson repeatedly refers to services as "products". Why? Public services, the domain of this discussion, are definitely services. Not products. What we pay for with our taxes are services. Whitehall is a service organisation. Not a factory. Ditto local government.

To be fair, that is of minor interest to Mr Thompson. It's not the services he cares about, but the exciting "ubiquitous web-based infrastructure to enable commonly shared capabilities":

With his "clear methodology" explained, Mr Thompson moves on to the "clear operating model and enabling methodology" which is needed to "prime the pump" of the "digitisation engine". The trick is to identify the "public organisations with the highest clusters of potential shared capabilities (SC)", which means developing a "digital profile" for each public organisation.

Achieving more of this sort of service model will require a rigorous distinction between “product” – essentially, bespoke services - and shared capabilities, which are far more important for achieving digitally-enabled public service redesign ...

... everyone can gradually maximise shared capability (platforms), and minimise departmental “product” (bespoke services) ...

The gradual maximisation and consumption of shared capability must therefore be the primary concern and stream of work for all transformation activities across the public sector. Although very important, improving “product” (bespoke services) is a secondary concern ...

Digital profiles look at first like Wardley maps but, instead of more or less visible value chain and evolution, this time you have to plot ubiquity against certainty, and draw an ogive on it:

The blue blobs, of course, aren't user needs. User needs are long gone. They're products, i.e. services, or capabilities.

What you're looking for is organisations with "promising clusters" (PCs).

Once you've found a couple of them, you develop a single system which they can share. At which point, the blobs stop being blue. They get greyed out. And here at last is the answer to our first question, what is Gaap. As Mr Thompson tells us, these greyed out blobs "will literally constitute the government as a platform".

It's been a bit of a slog, perhaps, but well worth it. With GaaP:

All we have to do is ...

... we can expect radical disruption of the market, opening up opportunities for innovation and investment by citizens, public, private, and third sectors alike - unleashing unprecedented innovation, efficiency, and savings ...

There are enormous opportunities for rationalisation and simplification across government ...

... and within a generation:

• Identify & agree existing, vertically siloed business models for each public organisation

• Convert these into digital profiles, and;

• Add the segmented profiles into separately-run backlogs

... which is what we all want because:

This will encourage the evolution of a service architecture that is based on a service-oriented view, supports an ecosystem of providers around a core set of capabilities, and opens up access to a broad community through standard interfaces ...

He doesn't like silos, does he. Silos are 19th century DNA. Strange that Mr Thompson's own business comprises a holding company (Methods Corporate Ltd) with six separate subsidiary companies, or silos, under it. Look at the duplication that must lead to. Seven audits. Seven annual returns to Companies House. Seven payrolls to operate. Seven "enormous opportunities for rationalisation and simplification". Seven blue blobs all surely pleading to be greyed out.

The inescapable DNA of a digitally-enabled public service model is a set of clean, agreed, and common capabilities, distilled and evolved from the currently duplicated and siloed functions, processes, roles and even organisations that exist across government.

But that's irrelevant because, turning our attention once again to Whitehall, when it comes to GaaP ...

... and £35 billion p.a. is a lot of money. There's the answer to our second question, why is anyone interested in GaaP.

A rough and ready calculation suggests such an approach could save the UK £35bn each year – but the jury is still out on how best to go about making it happen.

How does Mr Thompson come up with this figure? Click on the link and you be the judge. It's all something to do with a Dutch community nursing agency, Buurtzorg, whose operation is unmistakably analogous to Whitehall offering public

The logic is impeccable. 1½ million useless public servants out the door and 35 billion quid off the deficit – that's GaaP.

The Dutch model has a ratio of back office to frontline workers of 30 to 7000. If the UK could adjust its ratio accordingly, it would need fewer than 23,000 back office staff to support 5.3 million frontline workers. Reducing the number of back office staff from 1.5 million to just 23,000 would generate possible salary savings of up to £35.5bn.

----------

Updated 23 May 2015

Remember Rural Payments

Writing in ElReg yesterday, GDS to handle Govt payments? What could possibly go wrong?, Andrew Orlowski says:

Armed with the Wardley-Thompson wisdom above, what do you make of the suggestion to create a government-wide payments platform?

Be afraid. The previous government’s “elite digital team” which so brilliantly borked most of Whitehall’s websites, and that failed to meet its own targets, may be put in charge of handling real money: your money.

New Cabinet Office Minister Matthew Hancock hinted at the opportunity at a gentle public grilling today. Although Hancock didn't mention GDS by name, he told the Institute of Government:

The Government has a multitude of platforms for paying people money. And receiving money. What we don’t have is a platform all across government for receiving and paying money. Departments collect debts, for example.

How is General Hancock supposed to devise a strategy without seeing where payments is on the value chain-evolution terrain? What is the payments digital profile? Is its certainty high or low? What is its ubiquity score? Where is it in relation to the ogive? How many back office staff can Whitehall get rid of? How much money will be saved? In what way will user needs be better satisfied?

And who should General Hancock put in charge of this battle? "Hancock didn't mention GDS by name", we are told. Hardly surprising. GDS is a front-end shop. They don't hold themselves out as experts in purchase ledger. And for good reason – it's not their bailiwick, GDS do user interfaces.

The general already has a procurement centre of excellence in the Crown Commercial Service:

GDS would just embarrass themselves if they accepted this commission. So they won't accept it.

The Crown Commercial Service (CCS) brings together policy, advice and direct buying; providing commercial services to the public sector and saving money for the taxpayer.

"What could possibly go wrong?", Mr Orlowski asks. Remember Rural Payments, Agile@DEFRA, GDS's Dunkirk.

"Be afraid"? There's nothing for us to be afraid of from that quarter. The whole idea is just a flight of Mr Orlowski's whimsical fancy.

Mr Thompson suggests that turning payments into a platform would unleash "unprecedented innovation, efficiency, and savings". Examples, please. Innovation such as what? What efficiencies? What savings?

General Hancock will no doubt demand a bit more detail before sanctioning the engagement. He won't want to find his troops tied down in a campaign of trench warfare for the next five years only to have nothing to show for it at the end.

Updated 26.5.15

Methods Corporate Ltd and its subsidiaries

Mark Thompson, the man who plots ubiquity against certainty and deduces that GaaP could reduce the UK deficit by £35 billion (see post above), is the strategy director of the Methods Group.

£35 billion? Every year? Really? The chief executive of the Methods Group, Peter Rowlins, has had to step in to calm down expectations. He has written an article, GaaP: it's not just about the platform, with Mr Thompson,

UK GaaP* is now £35 billion lighter. Not a mention. It's gone. Replaced with the more vanilla "potentially colossal savings".

How does HMG lock in these colossal savings? It's our old friends standardisation and consolidation. And a new one – deverticalisation.

----------

* Apologies for confusing any accountants who've dropped in. We're talking about Government as a Platform, not Generally Accepted Accounting Principles.

Updated 5.6.15

UK government not being transformed:

NAO finds digital not yet delivering Whitehall staff cost savings

... there is "little evidence" departments are making expected savings from digital services

A report by the influential National Audit Office (NAO) into central government staffing costs has warned that despite the extensive work going into digital services across Whitehall, those efforts have yet to deliver significant staff cost savings.

Although the government expects digital services to reduce staff costs by processing transactions efficiently and introducing more customer self-service, with departments developing and implementing digital exemplars, so far, the NAO says, "we have seen little evidence that departments are making the expected savings." ...

The NAO has previously pointed out that for digital services, particularly in relation to efforts in moving towards Government as a Platform , there must also be a convincing economic case as well as a vision behind the government's digital strategy. Although at a macro level, the potential for cost saving is high, it was "missing learning and case studies from individual service transformations."

Updated 5 April 2018

It's been a long time, over three years, since Mark Thompson, please see above, told Guardian newspaper readers on 12 February 2015 that there are far too many non-performers on the UK public payroll and that "reducing the number of back office staff from 1.5 million to just 23,000 would generate possible salary savings of up to £35.5bn".

Last week saw the publication of Better Public Services, The Green Paper accompanying Better Public Services, A Manifesto.

What's changed?

The £35.5 billion p.a. figure has become £46 billion: "taking our public services as a whole, assuming a similar 14% of our total 2018 government spend of £814bn goes on management and administration, streaming just 40% of this could save £46bn year-on-year" (p.35).

If £35.5 billion gets rid of 1½ million useless staff, then £46 billion must allow us to part company with something like 1.9 million of the blighters, 400,000 more. Unfortunately, as there were only 23,000 of them left after Mr Thompson's previous putative clear-out, that's impossible. On the other hand, who's going to say no to £46 billion?

How will we know which staff to get rid of? Easy: "Public value assesses services from the citizens’, not the managers’, end of the telescope. Put simply, unless you add public value, your tenure within the state is negotiable" (p.38).

How do you measure public value? Obviously you use a "public value index" (p.86). And how do you create that index?

Never mind, the important point is that "both the digital commons and Public Value Index would be dead in the water without energetic support from a team of perhaps 25 to 30 peripatetic specialists who live and breathe capability mapping and open architecture" (p.93). It is understood that Mr Thompson would be one of those energetically peripatetic capability cartographers and that the rest might be close friends or employees of his at the Methods group of companies. That, at least, should be clear even if you're struggling a bit with the concept of the "digital commons".

What hasn't changed is the redemptive quality of the internet, the lessons from which teach us how to operate public services. At least that's the assumption. "The arrival of the internet enables people to exchange value in more direct ways that bypass traditional, command-and-control models ... This was foreseen by Marx, who explained how technological innovations eventually undermine monopoly situations" (p.25).

That assertion may surprise you a little. After all, it is precisely the technological innovations of the internet that have created the monopolies enjoyed by Amazon, Google, Facebook and the like. It is capitalist anti-trust laws that broke the late 19th century US monopolies and which may yet need to break today's. Nevertheless, "we think Marx, and the notion of economic rent, is as good a place as any for us to start" (p.37), so forget it.

Marx has been added in this latest version of Mr Thompson's dream: "What if our public services became as flexible, streamlined and easy-to-use for citizens as Uber – but with higher wages and in public ownership? As efficient as Amazon’s operations, and as intuitive as Google – but with 100% of the money invested into ethical and trusted public services, instead of pocketed by shareholders and a small elite of businesses? And all while securing and protecting citizens’ personal data, working with us in partnership, rather than monetising and exploiting our personal information like the worst of the private sector?" ...

... but sadly there is no mention any more of "promising clusters", please see above, ...

... and no recognition of the historical fact, inevitable or not, that, for 100 years, ethical and trusted Marxist politicians the world over have destroyed their national economies, starved their populations and terrorised and massacred them, while capitalism, replete with its hated profits and shareholders and tax payments, tends to feed, clothe, warm, pay, look after the health of and educate people.

"A Victorian civil servant awakening from a lengthy slumber would find the way our public sector still works comfortably familiar: largely centralised, hierarchical, and organisation-centric" (p.8). Nonsense.

That civil servant would be astonished at the colossal size of the 21st century UK state. Why does it have to be so big? It's not as though there's an empire to run. How can the gentleman in Whitehall claim to know better than the people what is good for them? Is public administration for an entire country comparable to running a nursing agency (Buurtzorg, please see above), as Mr Thompson continues to believe? Are the internet giants the right model to copy? Take away the monetisation of personal information and they wouldn't be giants any more.

And that civil servant would be astonished at the loss of power in the UK's local government. Mr Thompson wants to finish the job by obliterating local government in the name of efficiency. All that duplication? It's got to go: "the Marxian perspective implies that a managerial and administrative 'class', located across both public and private sectors, extracts 'rent' from frontline public employees, as well as from the public they serve" (p.24).

Enough.

Enough of this mendacious bilge.

In addition to the green paper we've been quoting from, there's a manifesto and a set of blog posts, including this one (sadly) by Jerry Fishenden and this one: "These final documents are the work of Jerry Fishenden, Mark Thompson and Will Venters. However, they draw upon valuable insights, critiques, pushback, feedback and improvements contributed by Andy Beale, Alan Brown, James Duncan, James Findlay, Sally Howes, Renate Samson and Simon Wardley. And some others who prefer to remain anonymous".

The starting point for Messrs Fishenden, Thompson et al is that the Government Digital Service has failed to transform government: "The recent efforts of the Government Digital Service have had little substantive modernisation impact, ultimately reverting to the usual displacement activity of website redesign and tinkering on the periphery of government by updating the look and feel of the central government website" (p.17). Their nostrums would fare no better.

No comments:

Post a Comment